Wu Shanzhuan:

“Deficit Character” & “Silent Ocean” (II)

Duration: 3 JUNE 12:00 AM

- 2 JULY 11:59 AM (CST), 2023

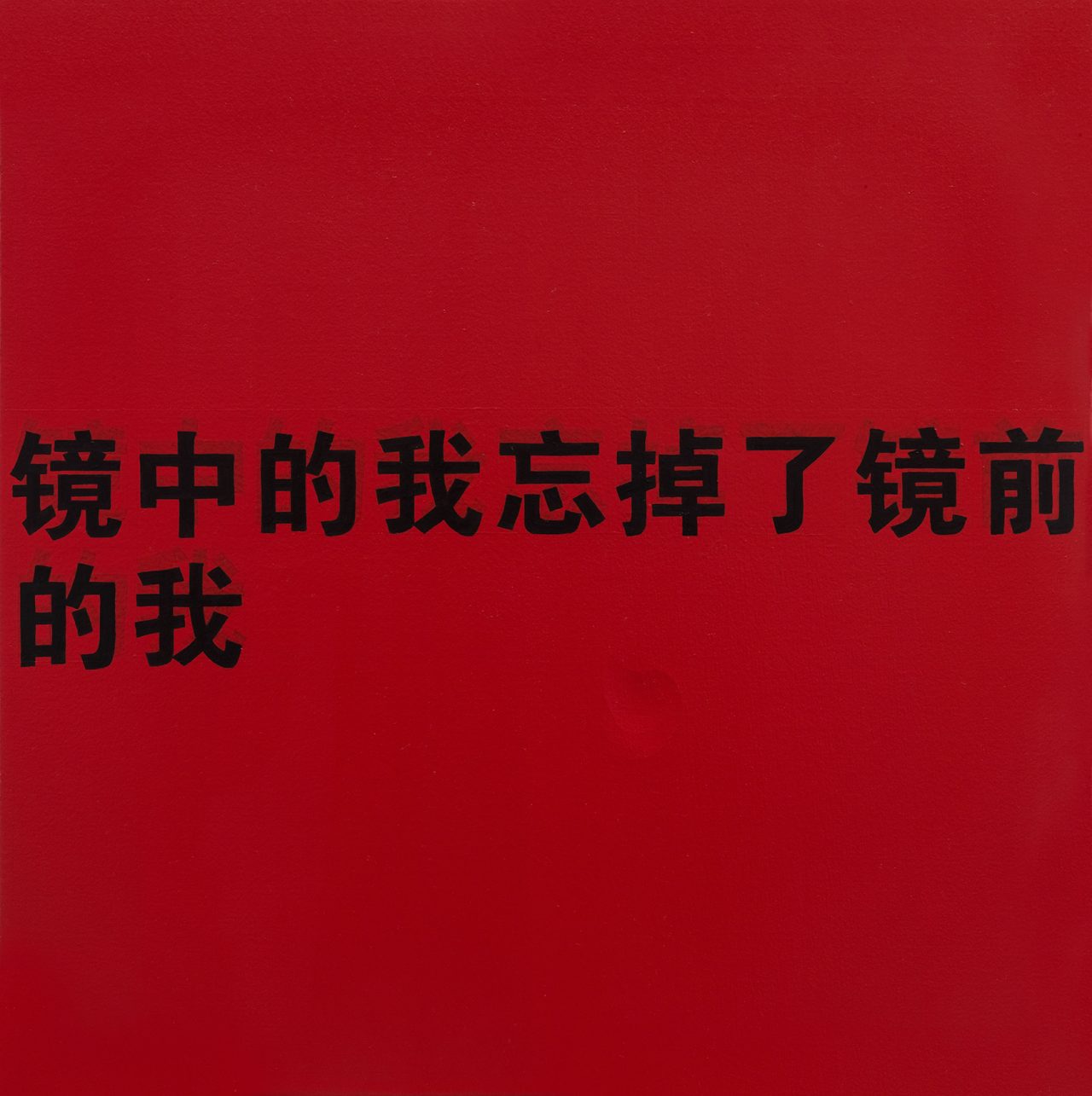

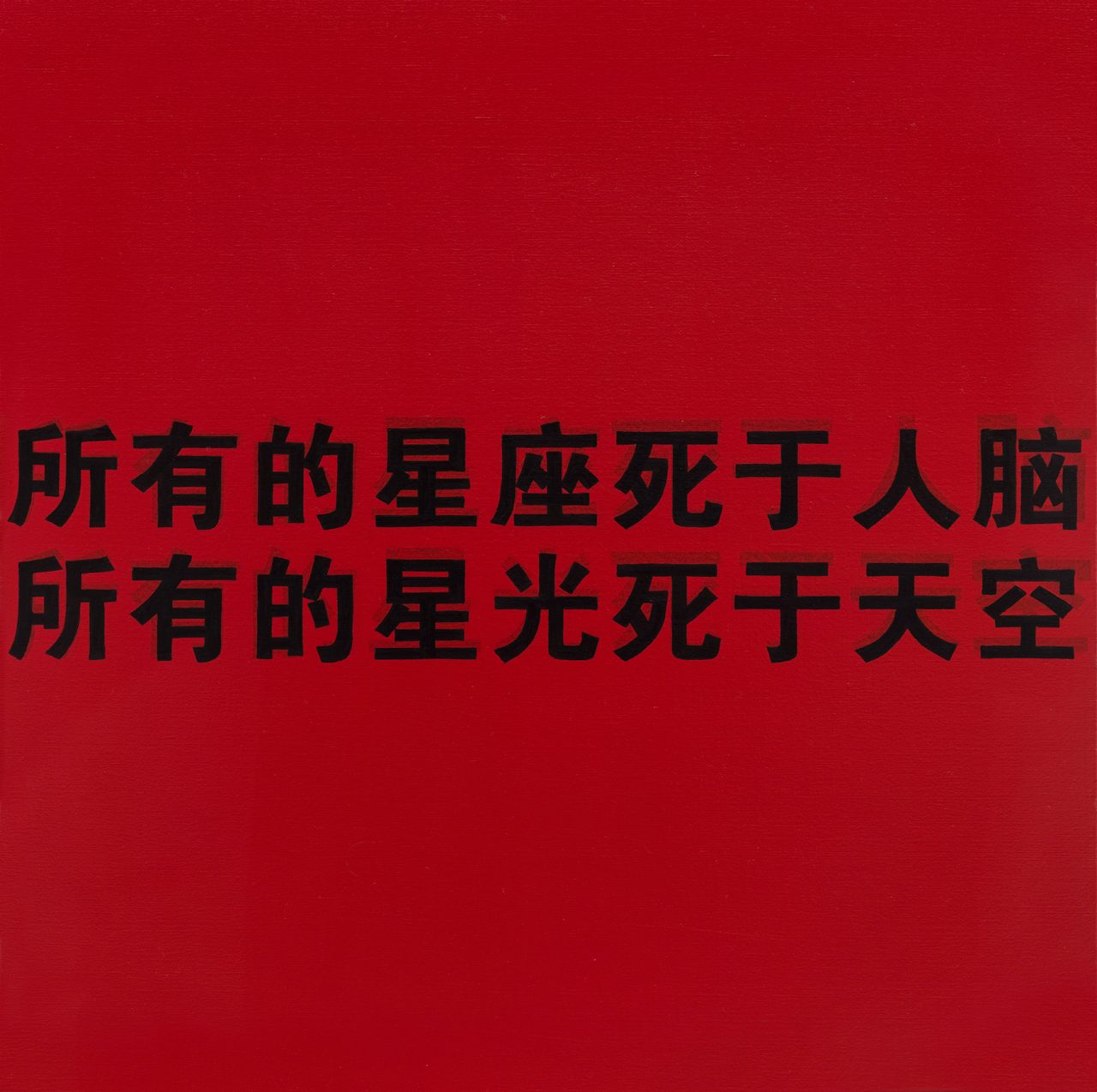

"Word" is perhaps an overly Westernized expression. In Wu Shanzhuan's Chinese linguistic territory, the basic element is in fact the Chinese character, or logograph. The "strictly monosyllabic pronunciation and unique structural formation" of Chinese logographs are Wu Shanzhuan's main sources of inspiration. The former characteristic of the logograph Was extensively employed by classical Chinese poets in creating homonym-based hymes in poetic couplets—a matching of both sound and sense. These constitute a marvellous kind of word game, a representational system of manifold meanings and multi-dimensional expression.

The latter characteristic—that is, the structural nature of the logograph in which the brushstroke forms the individual structural unit—allows for almost demonic powers of transformation, and also gave rise to the age-old system of creating characters. From the formalism of auspicious character iconography such as "the boundless blessings image" (wan fu tu) and the "longevity image" (wan shou tu), to the symbolism of the propitious characters of folk culture and Daoist talismans (fu), Chinese characters always maintain the tension between meaning and image. Stretching this a bit, Wu Shanzhuan's deficit (red) characters can also be considered as part of this character-creating tradition—but within their context, as representing a personalized ideological response to the conditions of the artist's own times.

From the gross physical point of view, the types of characters used in Wu Shanzhuan's works are either "boldface" (hei ti zi) black characters or modified boldface characters. This character style, composed of thick, even strokes, belongs to the genre of modern print-type and is far removed from the calligraphic tradition. In modern Chinese, boldface characters are usually employed as striking headlines and seldom used as body text. If they are used in body text, this readily denotes an emphasis, Boldface characters are strongly persuasive, solemn and authoritative. Their very qualities of regularity and strict respectability make them the first choice for use in political announcements, slogans, and the like, where words must convey an authoritative quality. In China, large, red boldface characters, in particular, denote the highest authority.

In December 1977, during the era of Hua Guofeng, the "The Second Simplification of Chinese Characters (Draft) Proposal" was issued and implemented for a short time. Not long after, orders came down that the effort should be halted and the proposal abandoned. The damage had been done, however, and the poison of those nonsensical simplified characters had already spread throughout the entire country. For Wu Shanzhuan, the sense of absurdity produced by the forced attempts to decipher those re-simplified characters was an exquisitely effective vehicle for bringing home the absurdity of reality during his formative years. The miswritten characters that appear in many of Wu's works are in fact taken from that same abandoned 1977 series of simplified characters—nonsensical simplifications that completely disrupted the accustomed channels of comprehension, frustrating legibility and causing injury to reason. The sense of anxiety experienced by people faced with characters that look readable but really are not, is deliberately made use of by Wu Shanzhuan; and he in fact reinforces this quality, creating word-images that are once impalpable to reason and yet visually graspable. This is the physical meaning of the deficit (red) character: it first and foremost implies a draining of the accustomed semantic meaning of the character, or, as Wu Shanzhuan puts it, the character becomes "deficited" of meaning.

--Excerpted from Qiu Zhijie's Wu Shanzhuan's Subjects and Systems.

About Wu Shanzhuan

Wu Shanzhuan (b. 1960, China). One of the key figures of the '85 New Wave Art Movement in China, Wu Shanzhuan's practice defies use of conventional visual art terms such as "watch", "stare" and "experience" to engage with. Instead, pulling together street smartness, intellectual experimentation and the spirit of the absurd in contemporary art, Wu Shanzhuan and his collaborator Inga Svala Thorsdottir draw you into a world where "read" becomes the key term. They are not creators of visual spectacles, but rather overthrowers and discoverers of truths and propositions, as well as counterfeiters of ideology and interpreters of everyday theology.

Wu Shanzhuan defines himself as criminal, intermediary, tourist and labor. The works Wu Shanzhuan creates are not the granted artworks but rather "Wu's Things". From the large number of "Wu's Things" made in the early 1990s, we see a desire for full opening and "transcending the boundaries" and his obsession with mathematics and logic which brings a strange sense of truth to his works. For a society dictated by a variety of faiths and customs, this is an "adulterated" truth. Wu never tires of quoting from Sartre: "People are a bundle of useless passion". The use for his useless passion is to find "useless truths". For more than 20 years, Wu Shanzhuan has used the forumulas "pseudo-words", "thing's right(s)", "parthenogenesis", "secondhand water", "tourist information", "perfect bracket" and "bird before peace", all of which are "useless truths", to weave his personal ideology. This ideology constitutes a profound critique to the system of concepts and experiences that we are accustomed to.

In the era when conceptual art generally faces a rethink, the works attest a vibrancy of concept and the power of thoughts. It is a rich collection of intriguing humor and sharp wit, spontaneous anti-metaphysical actions, insights into everyday politics, sensitivity to invisible workings of power systems and adherence to the fundamental state of democracy.

Wu Shanzhuan:

Deficit Character & Silent Ocean (II)

Duration: 3 JUNE 12:00 AM

- 2 JULY 11:59 AM (CST), 2023

"Word" is perhaps an overly Westernized expression. In Wu Shanzhuan's Chinese linguistic territory, the basic element is in fact the Chinese character, or logograph. The "strictly monosyllabic pronunciation and unique structural formation" of Chinese logographs are Wu Shanzhuan's main sources of inspiration. The former characteristic of the logograph Was extensively employed by classical Chinese poets in creating homonym-based hymes in poetic couplets—a matching of both sound and sense. These constitute a marvellous kind of word game, a representational system of manifold meanings and multi-dimensional expression.

The latter characteristic—that is, the structural nature of the logograph in which the brushstroke forms the individual structural unit—allows for almost demonic powers of transformation, and also gave rise to the age-old system of creating characters. From the formalism of auspicious character iconography such as "the boundless blessings image" (wan fu tu) and the "longevity image" (wan shou tu), to the symbolism of the propitious characters of folk culture and Daoist talismans (fu), Chinese characters always maintain the tension between meaning and image. Stretching this a bit, Wu Shanzhuan's deficit (red) characters can also be considered as part of this character-creating tradition—but within their context, as representing a personalized ideological response to the conditions of the artist's own times.

From the gross physical point of view, the types of characters used in Wu Shanzhuan's works are either "boldface" (hei ti zi) black characters or modified boldface characters. This character style, composed of thick, even strokes, belongs to the genre of modern print-type and is far removed from the calligraphic tradition. In modern Chinese, boldface characters are usually employed as striking headlines and seldom used as body text. If they are used in body text, this readily denotes an emphasis, Boldface characters are strongly persuasive, solemn and authoritative. Their very qualities of regularity and strict respectability make them the first choice for use in political announcements, slogans, and the like, where words must convey an authoritative quality. In China, large, red boldface characters, in particular, denote the highest authority.

In December 1977, during the era of Hua Guofeng, the "The Second Simplification of Chinese Characters (Draft) Proposal" was issued and implemented for a short time. Not long after, orders came down that the effort should be halted and the proposal abandoned. The damage had been done, however, and the poison of those nonsensical simplified characters had already spread throughout the entire country. For Wu Shanzhuan, the sense of absurdity produced by the forced attempts to decipher those re-simplified characters was an exquisitely effective vehicle for bringing home the absurdity of reality during his formative years. The miswritten characters that appear in many of Wu's works are in fact taken from that same abandoned 1977 series of simplified characters—nonsensical simplifications that completely disrupted the accustomed channels of comprehension, frustrating legibility and causing injury to reason. The sense of anxiety experienced by people faced with characters that look readable but really are not, is deliberately made use of by Wu Shanzhuan; and he in fact reinforces this quality, creating word-images that are once impalpable to reason and yet visually graspable. This is the physical meaning of the deficit (red) character: it first and foremost implies a draining of the accustomed semantic meaning of the character, or, as Wu Shanzhuan puts it, the character becomes "deficited" of meaning.

--Excerpted from Qiu Zhijie's Wu Shanzhuan's Subjects and Systems.

About Wu Shanzhuan

Wu Shanzhuan (b. 1960, China). One of the key figures of the '85 New Wave Art Movement in China, Wu Shanzhuan's practice defies use of conventional visual art terms such as "watch", "stare" and "experience" to engage with. Instead, pulling together street smartness, intellectual experimentation and the spirit of the absurd in contemporary art, Wu Shanzhuan and his collaborator Inga Svala Thorsdottir draw you into a world where "read" becomes the key term. They are not creators of visual spectacles, but rather overthrowers and discoverers of truths and propositions, as well as counterfeiters of ideology and interpreters of everyday theology.

Wu Shanzhuan defines himself as criminal, intermediary, tourist and labor. The works Wu Shanzhuan creates are not the granted artworks but rather "Wu's Things". From the large number of "Wu's Things" made in the early 1990s, we see a desire for full opening and "transcending the boundaries" and his obsession with mathematics and logic which brings a strange sense of truth to his works. For a society dictated by a variety of faiths and customs, this is an "adulterated" truth. Wu never tires of quoting from Sartre: "People are a bundle of useless passion". The use for his useless passion is to find "useless truths". For more than 20 years, Wu Shanzhuan has used the forumulas "pseudo-words", "thing's right(s)", "parthenogenesis", "secondhand water", "tourist information", "perfect bracket" and "bird before peace", all of which are "useless truths", to weave his personal ideology. This ideology constitutes a profound critique to the system of concepts and experiences that we are accustomed to.

In the era when conceptual art generally faces a rethink, the works attest a vibrancy of concept and the power of thoughts. It is a rich collection of intriguing humor and sharp wit, spontaneous anti-metaphysical actions, insights into everyday politics, sensitivity to invisible workings of power systems and adherence to the fundamental state of democracy.